We talk to astrophotographer Chris Grimmer to find out how much work goes into a spectacular nebula image (spoiler: a lot)

More than any other kind of photography, astrophotography is about building. It’s unfortunately not a case of just noticing a spectacular space phenomenon, pointing the camera and slapping the button – you need to gather light and information, often for hours, all the while battling the demons of light pollution and cloud cover.

We wanted to know more about how it’s done, and when we saw this spectacular image of the Veil Nebula from astro expert Chris Grimmer we felt we had a perfect chance to find out, so we sat down with him and got him to spill the beans from start to finish. Read on as he tells us the story behind the shot…

On crafting the image

“This is what’s classed as narrow band imaging. Rather than seeing the full red green and blue colour spectrums you look at a certain bandwidth within one of them. So for instance within the red we capture the emissions from hydrogen, which is sort of a low-end red spectrum.”

“Narrowband imaging tends to use three filters – hydrogen, oxygen and sulphur. However hydrogen and sulphur are both within the red spectrum, with oxygen being a blue green, so to make an image showing all three you have to effectively form a false colour. So the hydrogen becomes green, the sulphur goes to red, and the oxygen becomes blue.”

“I think this one was [does some maths] a total of 13 hours of exposure time. That was spread over five separate nights, over the course of about two months. This takes a lot of patience! Before I go out I use multiple weather apps to check the conditions and get a fairly accurate picture of what’s going to happen.”

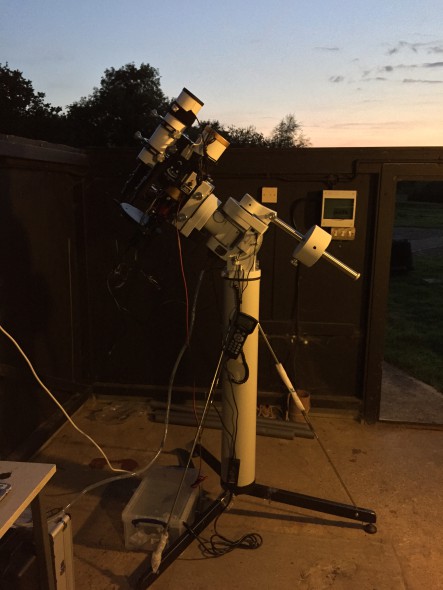

“The issue I have though is that where I live the light pollution is horrendous, so I have to go to Seething Observatory, the home of a large astro society of which I’m a committee member. I have keys to the site, so I have access to a shed where the roof comes off. So all I do is gather and pack up all my stuff into the car, take it up there, set it up, and I’ve got a nice dark site. Of course, that whole process takes about an hour and a half to two hours!”

On post-processing

“Each panel is thirteen different images, so I have software that stacks them on top of each other. I use software called Maxim DL – it takes the images, looks at the stars in the field of view and uses them to work out the exact coordinates of the image. It does that for each image and then overlays them.”

“Post-processing takes about six hours. Once Maxim has stacked the images I get a basic image of each colour channel. I then have to take them from Maxim, put them into Photoshop and do all the stretching with data levels and curves. At this point I’ve still got two black and white images, and I have to duplicate them and merge two of them together to create the false green, then colourise and combine them to get the RGB image.”

“It’s a lot of work…“

On the equipment

“This is taken on a Starlight Xpress Trius-SX694. It’s a specialist astro camera, a CCD chip camera that has coolers that will hold the temperature of the chip at about -10°, which helps reduce the noise in the pictures. It looks nothing like a camera, more like a coke can chopped in half, but it would cost two and a half grand to replace. It’s up there with high-end DSLRs, specially designed to do what it does.”

Chris’s setup. William Optics GT-81 refractor telescope, Starlight Xpress SXVR-H694 mono camera, iOptron CEM60 mount

About the Photographer

Chris Grimmer is an amateur astronomer, astrophotographer and photographer based in Norfolk. Follow him on Twitter and see more of his images on Flickr, Instagram and his website.