Landscapes looking like everyone else’s? In an extract from his new ebook, Niall Benvie explains what you can achieve by deconstructing the scene and presenting each element on its own.

The principle

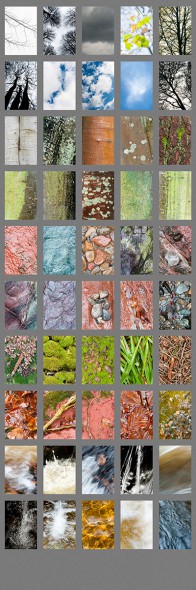

Deconstruction presents the landscape in an entirely fresh way. The many elements that comprise it are shown in explicit close up, rather than diminished by a wide-angle lens, providing the viewer with a detailed account not of topography or form, but of the fabric of the place. These elements are brought together in a large composite image, arranged according to their position in the landscape.

The practice

The elements of the composite are more akin to visual notes than conventional photographs. Ask yourself what a non-photographer moving through this space might notice and comment upon. Those are your subjects.

Break the location down into a number of zones – perhaps the sky, tree trunks, rocks, water, the ground at your feet: whichever parts of the scene are most detail-rich. The piece gets its impact from the massed effect so no individual image should “take the lead”.

On the face of it, deconstruction resembles the chocolate bar effect we looked at in the previous chapter. There is, nevertheless, a fundamental difference: deconstruction (as described here) is place based. The variety it describes is in the context of the whole landscape rather than a particular species of tree or type of rock.

The intention is different too; we want to reflect better the experience of that place by non-photographers, people who aren’t necessarily there at dawn or dusk and don’t see everything in terms of foreground, middle distance and background. This makes the content easier to relate to than in idealised ‘views’. Deconstructions complement regular landscape photographs by highlighting what they diminish – and not showing what they portray; landforms and extraordinary light.

The way you shoot for a deconstructed landscape photograph is quite different from a conventional one – and very liberating. For a start, you’re not looking for perfection; you’re searching for the ingredients to make a cake rather than lots of ready-baked ones. It’s useful to go out with someone who is interested in that place but isn’t necessarily a photographer; adopt their perspective and photograph what they comment on.

There is no need, either, to shoot only in the low light of dawn and dusk. Instead, bright diffused light is much better at revealing detail and rainfall is excellent at enriching colours. Gathering all the elements you need for a large panel will take several visits and it is a big advantage to be able to shoot each time without being hindered by the ‘wrong’ conditions.

Perhaps the biggest attraction of creating deconstructed landscapes is the possibility to create novel work that is hard to replicate, in places that have already been heavily photographed – and that could just as easily be your neighbourhood woodland as Bryce Canyon.

The Process

Deconstructions that encompass the whole landscape are time-consuming to make and, indeed, that is part of their attraction; they force a much closer, more thorough examination of a place than is needed in a ‘normal’ landscape photograph. This is how you connect with it and how distinctive work is produced. Perhaps, though, you don’t have the time or inclination to devote to making these big pieces. That being so, consider a more modular approach in which you focus on just one zone and photograph it in depth. Next year you may go back and shoot another of the zones until you eventually have all the pieces you need to assemble a complete deconstruction.

When you come to assemble the final piece you’ll have to decide whether the images work better pressed together or separated. I find that separation gives the viewer a chance to draw breath between each element, making the piece more comfortable to look at. Ideally, the background colour you use shouldn’t draw attention to itself; a mid-tone grey is often a good option.

Adobe InDesign, the industry-standard page layout application, is ideal for assembling deconstructions but relatively few photographers subscribe to it. You can also use Photoshop, but if you are a PC user you may be interested in an excellent, free program written by my friend Jack Moskowitz called Objectograph Grid Maker that makes assembly a breeze.

This is an edited extract from Niall’s new e-book, You are not a photocopier: From snapper to artist in six lessons, available for £9.50 for the high-resolution version and £8 for the standard version. For more information on Niall and his work, visit his website or read his blog.